You are viewing 1 of your 3 articles before login/registration is required

The Beacon of the Blind

My fight for the rights of women and girls who are blind and partially sighted, inspired by growing up with sight loss in Ghana

I have been advocating for disability rights since 1975. The main focus of my work has been improving the quality of life and strengthening the voices of people with disabilities, particularly women and girls. Although one might think that other disadvantaged groups – such as women without disabilities or men with disabilities who have experienced discrimination – would be more inclined to appreciate the struggles faced by women with disabilities, and in particular women with visual impairment, this is not always the case. As a result, I have often found myself advocating within the organizations for people who are blind and various women’s groups to create spaces and opportunities for women and girls who are blind and partially sighted and to secure and protect their rights.

My roles and achievements

In 1981, as part of my work with the Ghana Society for the Blind, I helped establish the Ghana Blind Women’s Work, which eventually became a full arm of the Ghana Blind Union. I was elected secretary of this initiative and, seeing how useful it was, I transferred that learning and experience into my work with the Africa Union of the Blind. When that organization’s first committee focusing on women and girls was established in 1994, I again acted as secretary and, two years later, I became the first female Vice-President of the Union. In that role, I worked assiduously to ensure that women would have a place and voice within the Union.

In 1997, I was appointed Vice-Chair of the World Blind Union’s Women’s Committee. Even though my tenure as Vice-Chair is long past, I still work as a technical advisor to the World Blind Union, helping to formulate and implement policies and empower women and girls with visual impairment. In Ghana, I am part of a group of women with disabilities who examine and improve statements on women and girls with disabilities to be incorporated into policies and laws to ensure their inclusion. We have undertaken this process for the UN’s fifth Sustainable Development Goal, the Africa Disability Protocol, and other articles.

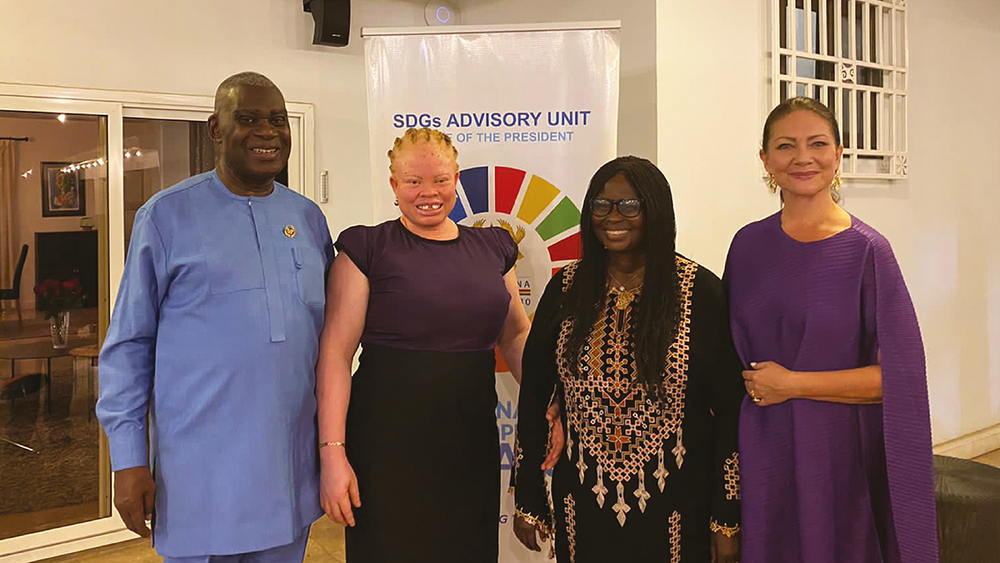

Currently, I am a member of the UN’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), fighting for inclusion and increased opportunities for women and girls with disabilities. Before I joined the CRPD, only one of its 18 members was a woman. I also participated in the “Equal UN” Sightsavers campaign, which resulted in the election of six women to the CRPD in 2018. I continue to be part of the campaign in subsequent elections; now that we have reached gender parity on the committee, we are focused, among other areas, on improving the substantive content on the rights of women and girls with disabilities in the work of the committee and that of some identified treaty bodies.

Last year, I received the World Blind Union Women’s Empowerment Award, a great honor that I dedicated to all women and girls who are blind and partially sighted working at the grassroots to make change, and to all the women and girls with disabilities who have worked alongside me throughout my career.

So what originally inspired my advocacy work?

The beginnings

I grew up with my grandmother in a community in the south of Ghana, a two-hour drive from the capital, Accra. I first noticed a decline in my eyesight when I was 10, which led me to seek medical attention. I was given reading glasses, but my eyesight declined so fast that I required new glasses every three months. By the time I was 14, at the Ghana Secondary School in Koforidua there were no longer any glasses available that would improve my sight, so I struggled through high school. Because I couldn’t read from the blackboard or any of my textbooks, I instead had to rely on those teachers who were willing to take the time to complete extra work with me, and on my classmates for the classes in which my teachers ignored my presence completely.

Before I took my exams, my school attempted to liaise with the examination board so I could be given papers in large print – something that, alongside my own handwriting, I could still read at the time. However, this didn’t happen, so I was left to struggle through my exams. At this point, my family decided it would be best for me to attend the School for the Blind to learn to typewrite and to read and write Braille. I didn’t view joining the School as a negative development. I had grown up in that community and had classmates whose parents taught there, which meant that I’d previously encountered people who are blind and never considered blindness to be anything regrettable. But all this changed in 1975. I was 17 at the time and, one day, three members of my extended family met me at the gates of the school. When asked why I was there, I explained that I’d enrolled at the school, and the way they responded really took me aback. Their words were harsh and cut deep. I could see that they saw me as a brilliant person with many prospects and a bright future, but the loss of my vision also led – in their eyes – to the loss of those qualities. I internalized those sentiments and, by the time I got back to my dormitory, I was in tears. I truly felt like my life was over before it had even begun.

Some time later, I was visited by a young woman from the College of Education, who was blind. She told me that she’d just graduated from the Wenchi Methodist Senior High School, an integrated school for people who are visually impaired in Ghana. An examiner who came to my secondary school to supervise examinations told her about me, and the story made such an impression on her. It was her desire to meet me, so when she heard that someone had completed secondary school and had come to the school for the blind, she came checking if I was the one she had heard of.

Seeing her in her uniform and hearing her talk of how she had enrolled in college, I had hope. For the first time in a long time, I believed I had a future. That meeting was really meaningful to me because, growing up, I wanted to be a teacher, a journalist, or a lawyer. I had cast those dreams aside as fanciful thinking, but here was someone who was totally blind and yet on her way to success in one of those professions. It reignited my passion and got me to refocus. It also made me realize that, if one person’s presence and intervention was so significant to me, maybe I could pass this on to others by mentoring and influencing change. This is what led me to advocacy.

Women and girls with disabilities face a double dose of discrimination. Many educated women with disabilities are not employed and few have the opportunity to access technology. Often, women with disabilities’ input is dismissed or ignored. In addition, women and girls with disabilities are at a greater risk of gender-based violence and abuse. This is why empowerment and implementing change is so important to me. When we are empowered, we gain self-awareness, assertiveness, and confidence – and we can climb out of the deep holes into which we have been pushed. I know the truth of this, having experienced it myself, and I will continue to work to make sure that every blind and partially sighted woman and girl knows that she has a future.

The New Optometrist Newsletter

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here