You are viewing 1 of your 3 articles before login/registration is required

Spider Sense

How does a jumping spider study help us understand the pathophysiology of dry AMD?

Elaborating on our understanding of the role of nutrition (or lack thereof) in the onset of AMD, biologists at the University of Cincinnati made the surprising discovery that jumping spiders (Phidippus audax) lose light-sensitive cells when they are underfed (1). The discovery occurred while the researchers were examining bold jumping spiders using their lab’s own custom-made ophthalmoscope. “Really, we had been investigating the refractive properties of these relatively high-resolution eyes,” says Elke Buschbec, one of the researchers. “But then we noticed that some spiders had degenerated photoreceptors, particularly in an area where the photoreceptors are more densely packed.”

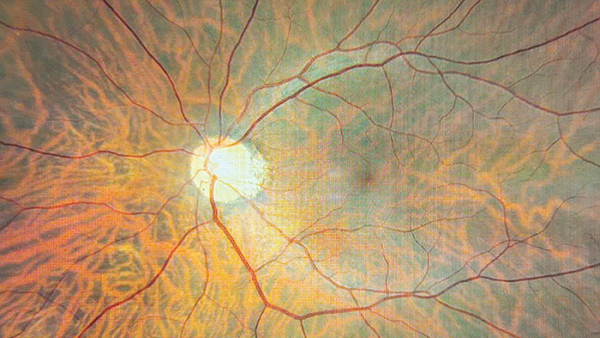

Jumping spiders, which rely on their superb vision for predation, present a compelling analogue model to study retinal and neuronal health in the human eye. The spiders can distinguish living and non-living things in their peripheral vision by relying on the same cues used by humans, and the anterior lateral eyes of these spiders use a single lens and feature variability in photoreceptor density. Much like the human macula, the spiders have a high-density region (HDR) located centrally in their retina. The study, published in Vision Research, found that the photoreceptor loss occurred most prevalently in the HDR – much like AMD occurs in humans – suggesting that this discovery could present an opportunity to explore nutrition’s role in combating retinal degeneration.

Though positive about the results from the study so far, senior author Annette Stowasser notes that carefully designed studies will be needed to understand exactly which nutrients are involved in the process – all while factoring in any other environmental factors that might play a part.

Although advances in anti-VEGF treatments have helped tackle wet AMD, there are still no FDA-approved dry AMD treatments available. Adding to the catalog of animal models for AMD research may help take us another step closer to unraveling the pathophysiology associated with the disease – and one step closer to preventing its progression. “Spiders are an interesting model as they are, in many ways, more tangible; the parallels are helpful to get to the basic mechanisms of photoreceptor degeneration,” Buschbeck notes. “In addition to our work with spiders, we have also been working with fruit flies, because they allow us to get better insights on genes that might be involved in these processes.”

This article first appeared in The Ophthalmologist

Reference

- S Rathore et al., “Nutrition-induced macular-degeneration-like photoreceptor damage in jumping spider eyes,” Vision Research, 206 (2023). PMID: 36758462.

The New Optometrist Newsletter

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Most Popular

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here