You are viewing 1 of your 3 articles before login/registration is required

Prioritizing Nerve Regeneration in NK

Early detection and advanced therapies are transforming the management of neurotrophic keratitis

The symptoms of neurotrophic keratitis (NK) vary by severity, generally related to the severity of corneal sensory impairment. Currently, NK is categorized into three stages of severity. Stage one is marked by punctate epithelial erosions, which lead to decreased tear production and a dry appearance on the ocular surface, yet with minimal corneal damage. Stage two consists of persistent epithelial defects that will not heal with conventional treatments, yet no corneal stromal involvement. Stage three includes corneal stromal involvement, corneal ulceration, stromal melting, and possible perforation (1).

Although considered a rare disease, NK may not be as uncommon as was once believed (2). As such, I believe that models should be adopted to classify patients with dry eye disease and persistent ocular epithelial defects as "early" or "pre-NK." This type of classification strategy could be considered similar to how patients are classified as pre-diabetic when their blood sugar is elevated to a certain range but prior to the emergence of more serious symptoms. If we identify patients at this earlier stage and initiate treatment straightaway, we may be able to prevent progression to symptomatic NK.

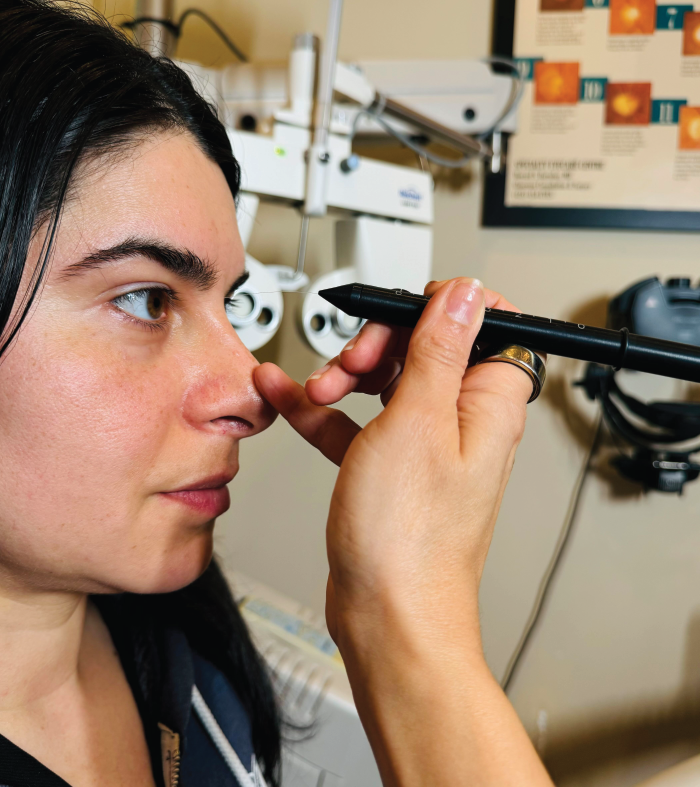

Many optometrists may not test for corneal sensitivity due to inexperience with the procedure or perceived difficulty, but the test is simple and can be done in the chair in less than a minute, with no need for any additional equipment. Corneal sensitivity can be assessed qualitatively by lightly touching the central cornea in four quadrants with a sterile cotton wisp or dental floss, and asking for the patient’s response. It can also be assessed quantitatively by using an esthesiometer, such as Cochet-Bonnet (see Figure 1), or a non-contact instrument like the Corneal Esthesiometer Brill. This simple procedure can help identify patients who may be on their way to developing NK so that treatment can be initiated before patients develop more serious symptoms.

Once a patient has been diagnosed with NK, the management of their condition depends on the stage of disease severity. In the first stage of NK, I would protect the ocular surface with lubricating artificial tears or perfluorohexyloctane drops (Meibo®; Bausch + Lomb), use corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and therapeutic contact lenses, and, if necessary, perform punctal occlusion. When the loss of corneal nerve sensation is detected, I initiate patients on biologic therapies like cryopreserved amniotic membrane (CAM; Prokera®; BioTissue), cenegermin (Oxervate®; Dompé), or autologous serum or platelet-rich plasma (PRP).

When I see a patient with early stage two NK or more severe, I typically apply CAM as a first step to protect the ocular surface and initiate the neuroregenerative process. CAM contains several growth factors, such as nerve growth factor, keratinocyte growth factor, and hepatocyte growth factor, which all promote corneal epithelial wound healing. CAM has well-demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anti-scarring, and pro-regenerative properties, and there are a wealth of studies showing they can successfully treat corneal epithelial defects and ulcers that were unresponsive to prior treatments (3).

After CAM, I treat patients with a course of cenegermin (for eight weeks of treatment six times per day). Cenegermin is a recombinant nerve growth factor and is the only drug currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of NK. In two clinical trials, almost 70 percent of NK patients treated with cenegermin achieved complete corneal healing in eight weeks (4). My clinical experience mirrors these results, where I’ve seen complete healing of the persistent corneal defects and improved corneal sensitivity after a course of cenegermin. It is important to remember that these patients will report an improvement in their vision as the cornea heals, but they will complain of worsening dry eye symptoms as their corneal sensitivity returns.

Next, I like to put my NK patients on autologous serum or PRP drops. A lot of the time, I will keep patients on these drops for longer-term regimen, as they may have a recurrence if they are susceptible to NK. Both autologous serum and PRP have shown favorable outcomes in treating NK, both in resolution of corneal defects and ulcers and improvement of corneal sensitivity (5, 6). However, we should keep in mind each patient’s individual circumstances, including what they can afford, as neither autologous serum or PRP are covered by insurance.

As a last resort, surgery should be considered for NK. But in an ideal world, we would be able to identify and treat NK early enough so that a patient’s condition does not progress to the extent where surgical intervention is necessary. If surgery is needed, corneal neurotization has shown promise in allowing patients to regain corneal sensitivity, eyelid movement, and visual acuity (7). This is performed via either transposition of the supraorbital and/or supratrochlear nerves or transposition of the sural nerve graft.

As we progress in our understanding of NK and recognize the disease as more common than previously thought, we must update our practices accordingly to ensure that we identify and treat patients early enough to prevent disease progression and associated vision loss. Now that we have a wealth of options for treating NK, just a few extra moments in the chair to check our patients’ corneal sensitivity could make a lifetime of difference for their vision and future quality of life.

The New Optometrist Newsletter

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Most Popular

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here