Eye On History: Oswald von Wolkenstein

The story of a one-eyed 15th century poet and knight-errant

The loss of an eye is a highly unfavorable outcome in ophthalmology because it affects stereopsis, visual field, and overall quality of life. So it is perhaps surprising to find that many of history’s most celebrated military commanders had monocular vision – typically the result of trauma.

We’ve recently reviewed famed military commanders who lost an eye, including Philip II of Macedon (circa 383-336 BC) and Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino (1422-1482). One, Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), may have exaggerated a minor injury for secondary gain, while another, Charles “Chuck” Yeager (1923-2020), suffered a “near miss.”

Here we consider Oswald von Wolkenstein (1376/77-1445), who served as a knight and soldier, but is best remembered for his poetry. He was a German minnesänger, who composed poems and songs of courtly love, similar to a troubadour or a knight-errant. He is traditionally considered either the last minnesänger or the first German Renaissance poet (1). Two of his manuscripts (one written in 1425, the second in 1432) have survived to the present day, which makes him the earliest known German poet with this degree of documentation (2).

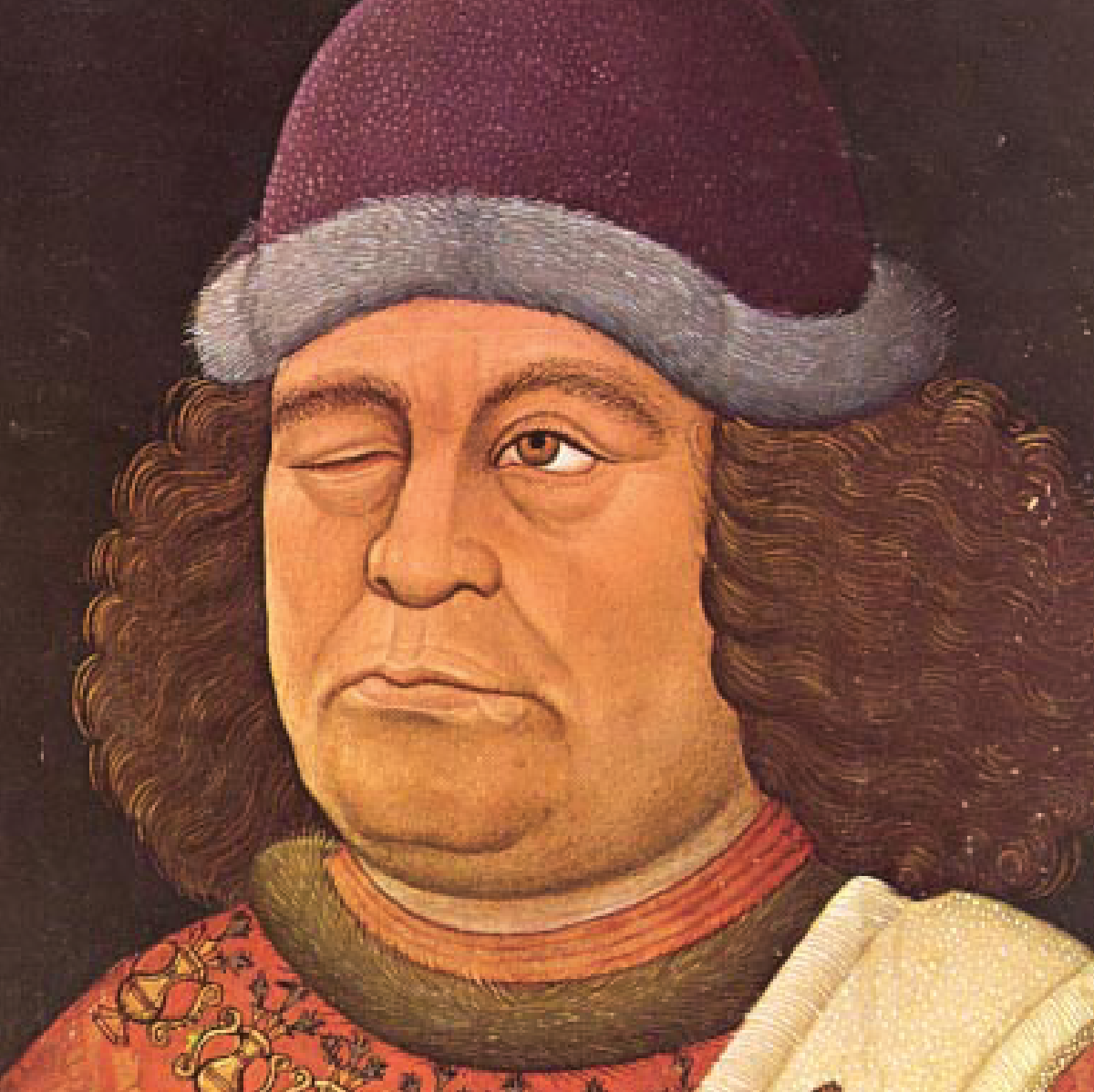

Exactly what happened to Wolkenstein’s eye is unknown, but many authors have described a serious trauma. In various accounts, a young Oswald is reported to have been stabbed by a dagger while looking through a keyhole at a couple making love (3) or shot with a crossbow “in some riotous carnival frolic” (4). One author suggested that he was the victim of domestic violence from his wife, Margareta von Schwangau (5). His best-studied portrait (Figure 1), from his 1432 manuscript, shows a complete ptosis with no view of the underlying eye. A (likely) more modern trophy based on this portrait (Figure 2) appears to show loss of volume behind the ptotic lid, as if to represent anophthalmos or phthisis bulbi.

Oswald was born in South Tyrol in 1376 or 1377, which was then part of Austria and today is located in Italy (1). He was the second son of feudal lord Friedrich von Wolkenstein and Katherine von Villanders. He is said to have spoken ten languages and played as many musical instruments. He became enamored with chivalry, and was said to have admired the legends of King Arthur and the Holy Grail (4).

In 1387, at the age of 10, Oswald joined a crusade led by Duke Albert III of Austria (1349-1395) and the Teutonic Order of Knights of the Holy Cross against unbelievers in Prussia and Lithuania. (He recounted his experiences in “Knight Errant” below.) Thus began his long career in a variety of military and diplomatic positions throughout Europe and as far as Persia (4). Probably the most important battle in which Oswald fought was the conquest of Ceuta, led by King John I (Joao I, 1357-1433) of Portugal, on the north coast of Africa at the Strait of Gibraltar in 1415 (2). Much of Oswald’s later career was in the service of Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368-1437), King of Hungary and later Holy Roman Emperor.

Oswald became engaged to Sabina Jäger in 1397, but she would not marry him until he completed a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He did this, fought bravely, and was dubbed Knight of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. However, when he returned to South Tyrol in 1400, he learned that she had married another man (Hans Hausmann) while he was away (4). He married Margareta in 1417, which made him an imperial knight (1). They had seven children (4).

During a renovation in the Neusift Monastery in South Tyrol in 1973, a tomb was discovered which contained the skeleton of an elderly male. A multidisciplinary team of investigators reported in 1982 that this was most likely Oswald’s skeleton. Only part of the right orbit was recovered, but the investigators reported no evidence of trauma or any disease that may have caused ptosis or an underlying eye injury (6).

English translations of selections from two of Oswald’s songs are reproduced below (7).

From “Knight Errant”

It occurred to me, when I was ten years old,

to see what the world out there might hold.

Down and out, in quarters hot and cold,

I lived amid Christians, Greeks, and heathens.

Three cents in my bag and small crusts of bread

were all I’d packed, as I forged ahead.

Among kin and foe red blood I shed

and often thought I’d perish from my lesions.

I traveled on foot until my father died,

near fourteen years old, no horse in sight,

except that mare I stole, pale dun of hide,

filched from me, after one short season.

From “Hardships I Now Endure”

All the honors bestowed on me

by sundry princes and queens,

all the good times I have seen,

I now atone for here beneath this roof.

My misery knows no end.

I need to get my wits about me,

since I have to scrounge for bread

and parry threats from every side,

with no red lips to console me.

This article first appeared in The Ophthalmologist.

About the Authors

Stephen G. Schwartz

Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Naples, FL, USA

Christopher T. Leffler

Department of Ophthalmology, Virginia Commonwealth University and Richmond VA Medical Center, Richmond, Virginia, USA

Andrzej Grzybowski

Professor of ophthalmology at the University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland, and the Head of Institute for Research in Ophthalmology at the Foundation for Ophthalmology Development, Poznan, Poland. He is EVER President, Treasurer of the European Academy of Ophthalmology, and a member of the Academia Europea. He is a member of the International AI in Ophthalmology Society (iaisoc.com/) and has written a book on the subject that can be found here: link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-78601-4.

The New Optometrist Newsletter

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Most Popular

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here