Are We Missing the Big Picture?

Why ultra-widefield imaging is essential for all

Dilated fundus exams are the very foundation of ocular disease evaluation. In fact, we are so accustomed to the DFE that we rarely consider whether we might be missing something significant.

But what if we are?

While chairing an interactive webinar on the applications of single-capture ultra-widefield (UWF) imaging, I polled the attendees (approximately 300 eye doctors) regarding their use of UWF (1). One question provided particularly surprising results. When UWF users were asked if they had ever found unexpected pathology in a patient with no visual complaints, 97 percent responded “Yes.”

For those unfamiliar with UWF, this statistic may seem hard to believe. For me, a retina specialist who has used this technology for 12 years, it is not. Indeed, I have this experience almost every week. I suspect that almost any UWF user would have a similar story to tell.

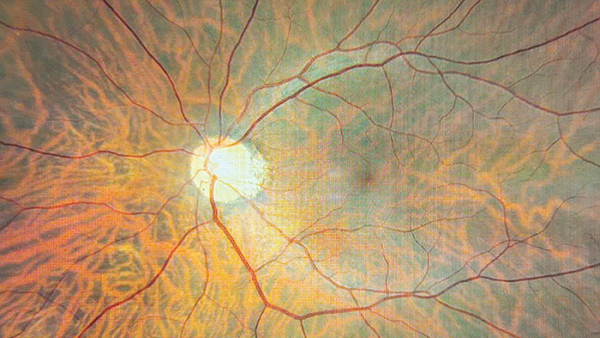

An UWF retinal image, as defined by the International Imaging Study Group, refers to one that encompasses retinal anatomy anterior to the vortex vein ampulla in all four quadrants (2). The Optos technology, which I use in my practice, produces a non-mydriatic 200-degree (80 percent of the retina) single-capture image in less than half of a second.

Though I spend nearly all my clinic days examining retinas, I am continuously surprised by what I find with this technology. On some occasions, I have found something that was missed on a previous exam. On others, it has been unexpected pathology in a patient referred for something else entirely. Using UWF images, I have identified undiagnosed nevi, lattice degeneration, and asymptomatic horseshoe tears – pathologies that often present in the far retinal periphery. I am not an over-tester, but these experiences have led me to order UWF imaging for every patient.

The ability to identify and document retinal pathology is paramount no matter the specialty. As demand for premium IOLs expands, cataract surgeons surely need to know the status of a patient’s retina prior to surgery. No one wants to find an undiagnosed epiretinal membrane in a patient with 20/30 or 20/40 vision after a perfect surgery. In the case of a spontaneous post-surgical retinal detachment, a pre-op UWF image documenting a healthy retina can confirm the detachment was not missed by the surgeon.

For general ophthalmologists, the majority of patients may have normal examinations, but for those who do not, the UWF image is incredibly useful for explaining the diagnosis and treatment recommendation, and even illustrating results by comparing pre- and post-treatment images. When a referral is needed, the image can help patients understand why they need to see a specialist.

When I receive UWF images from referring doctors, I’m able to quickly determine if or how urgently the patient needs to be seen, which also helps ensure efficient care by enabling us to more appropriately prioritize urgent cases. It also supports our referring colleagues by helping them avoid unneeded specialty visits.

One concern I have heard about single-capture UWF imaging is the equipment cost. Given that insurance generally does not cover routine imaging before a patient exam, this concern is understandable – but it is not insurmountable. In our practice, UWF has proven so valuable that we find it well worth writing off. Knowing we are not missing pathology enhances care and gives us peace of mind, and I’d argue that the documentation value of the images is priceless. Some general practices and optometrists build the cost of imaging into the exam fee; others offer it as a patient pay option. These doctors often report that patients ask for their image to be taken each year, despite the incremental cost. In general, patients are happy to make the investment in their eye health – particularly when they are about to make an even greater investment in something like a premium IOL.

Another common concern is about the time an additional diagnostic test might require. In my experience, using UWF has actually contributed to greater efficiency. Because UWF devices are easy to use and require little training, my staff capture the images in the work-up area (freeing our photographers for more technical work). And that means I have the opportunity to see the macula, optic nerve head, and peripheral retina before I even sit down in front of the patient, thus informing where I need to focus my DFE in advance.

Without question a dilated exam is indispensable. However, it requires time, is subject to patient cooperation, and forces us to rely on dictation to a scribe and/or illustration done from memory for documentation. The aging population coupled with a shortage of eye care professionals means that we are all under pressure to see more patients each day, making a thorough DFE even more challenging. In the face of these obstacles, we must remain focused on the big picture: Doing all that we can to ensure we are providing the best possible care for our patients. With this in mind, single-capture UWF imaging has become an invaluable part of my practice. I strongly suspect that at least 97 percent of those who use this technology feel the same.

This article first appeared in The Ophthalmologist.

References

- D Dhoot et al., Advances in Imaging Online Symposium, Pentavision, 2021.

- N Choudhry et al., “Classification and guidelines for widefield imaging: recommendations from the International Widefield Imaging Study Group,” Ophthalmol Retina, 3, 843 (2019).

The New Optometrist Newsletter

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Most Popular

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here

Sign up to The New Optometrist Updates

Permission Statement

By opting-in, you agree to receive email communications from The New Optometrist. You will stay up-to-date with optometry content, news, events and sponsors information.

You can view our privacy policy here